The history of men's suits in Australia is a narrative of adaptation and resilience. It is the story of a British sartorial heritage transplanted into a hostile, arid climate, and its subsequent metamorphosis into a distinct national style. For the Australian groom, the wedding suit has always been more than a garment; it is a cultural signifier that balances respect for tradition often rooted in Anglican or Catholic solemnity with the practical necessities of the Australian environment.

Table of Contents[Hide]

- 1. The colonial legacy and climatic tension

- 2. The role of the suit in Australian masculinity

- 3. The 1920s: The Jazz Age and the Struggle for Modernity

- 4. The 1930s: The Golden Age of Classic Menswear

- 5. The 1940s: Austerity, Rationing, and the Victory Suit

- 6. The 1950s: The Grey Flannel Suit vs. The Rocker

- 7. The 1960s: The Peacock Revolution and the Mod Groom

- 8. The 1970s: Disco, Ruffles, and the Anti-Suit

- 9. The 1980s: Power Dressing and the Corporate Groom

- 10. The 1990s: Minimalism and the "Recession" Suit

- 11. The 2000s: The Slim Fit Revolution and "Metrosexuality"

- 12. The 2010s: The Heritage Revival and the "Rustic" Groom

- 13. The 2020s (to Present): Post-Pandemic Individualism and Linen

- 14. Conclusion

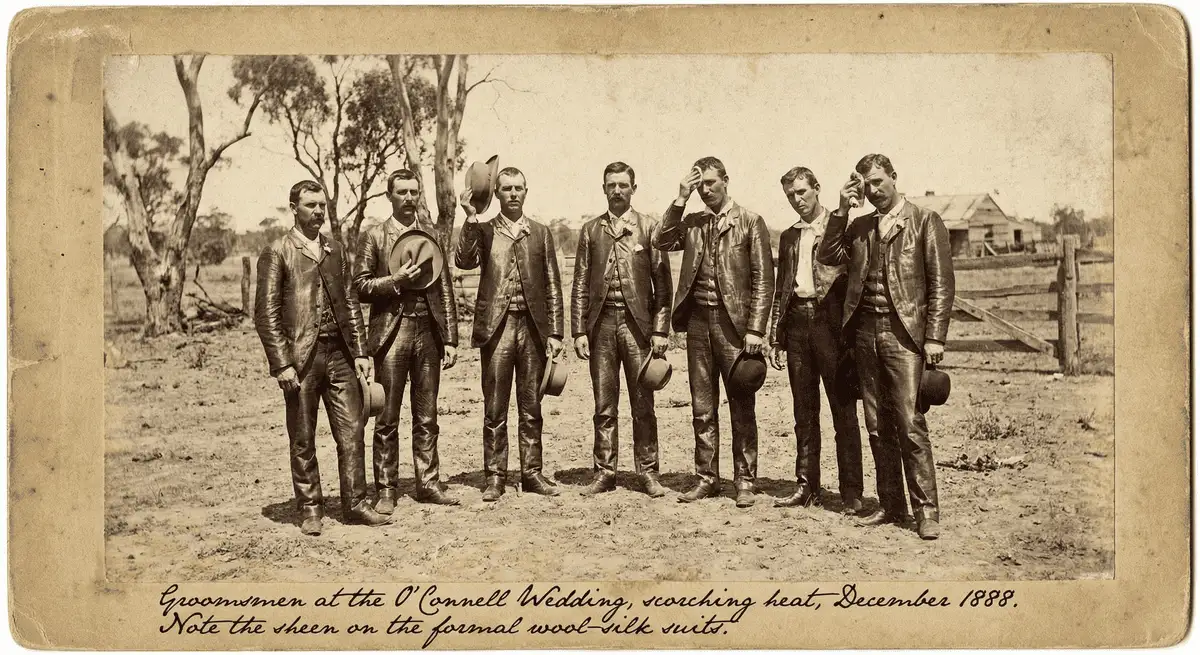

1. The colonial legacy and climatic tension

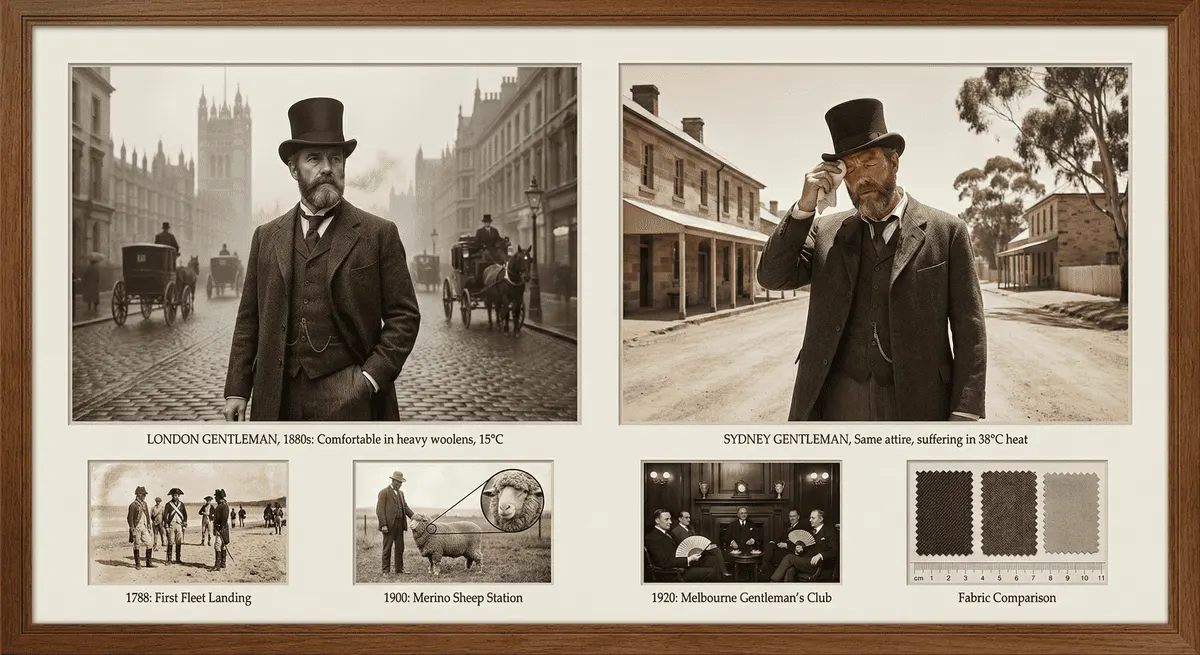

Since European settlement in 1788, Australian men’s fashion was dominated by a "cultural cringe" that deferred almost exclusively to British standards. Early settlers, convicts, and administrators wore heavy woolens tweeds and broadcloths that were entirely unsuited to the Australian heat. The colony was physically located in the Asia-Pacific but psychologically tethered to the North Atlantic. This created a persistent tension in formal wear: the desire to appear "civilised" and "correct" according to London etiquette versus the physical reality of scorching summers.

By the turn of the 20th century, while the silhouette remained British, the fabric composition began to shift. The development of fine Merino wool by local farmers allowed for lighter weaves, a crucial innovation that would eventually position Australia as a global leader in suiting fabric production. Yet, well into the 1920s, the pressure to maintain the stiff collar and heavy coat of the Mother Country was immense, viewed as a necessary armor of respectability against the "uncivilized" heat. The "Victorian" mindset persisted, equating physical discomfort with moral fortitude.

2. The role of the suit in Australian masculinity

The suit in Australia has served a dual purpose: as an equalizer and a differentiator. In a nation that ostensibly prides itself on egalitarianism the land of the "fair go" the wedding suit was one of the few occasions where the working-class male adopted the uniform of the aristocracy. However, unlike in England, where class signifiers were woven into the very cut of the cloth, the Australian approach to the wedding suit became increasingly pragmatic. The evolution of the groom's attire tracks the nation's broader social history: from the deferential dominion of the 1920s to the confident, multicultural, and globally integrated nation of the 2020s.

3. The 1920s: The Jazz Age and the Struggle for Modernity

The 1920s in Australia was a decade of dichotomy. On one hand, the trauma of the Great War (World War I) entrenched a desire for stability, tradition, and a return to "normalcy"; on the other, the "Roaring Twenties" brought an influx of American jazz culture and cinema that challenged Edwardian stuffiness.

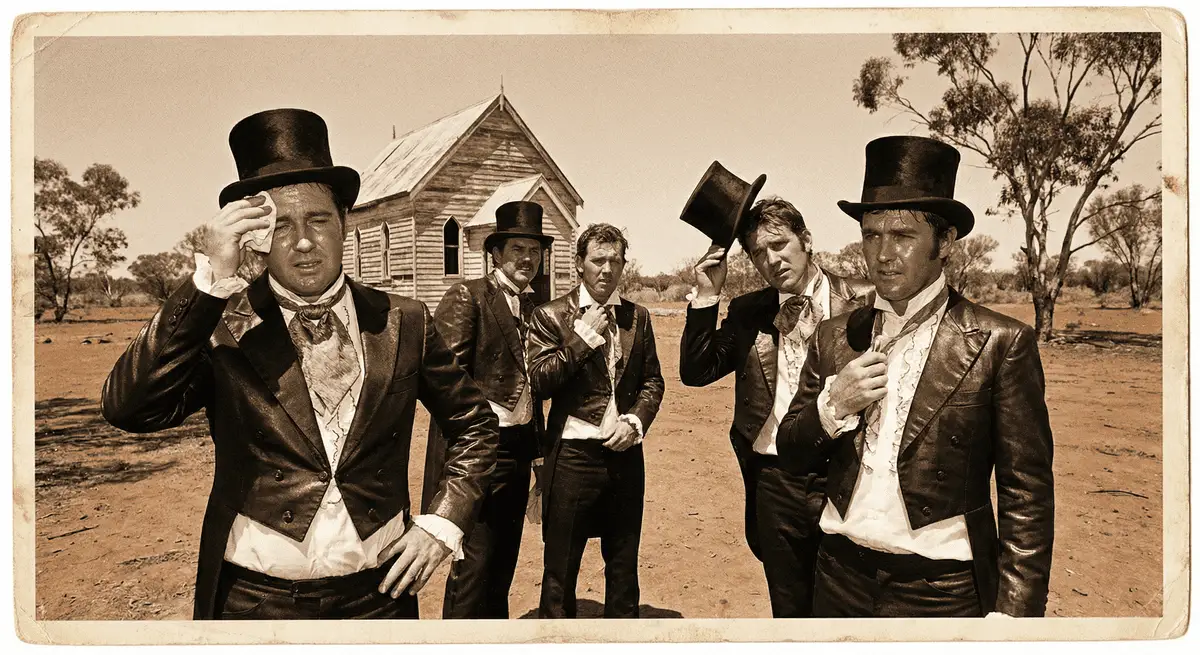

3.1 The Morning Suit vs. The Lounge Suit

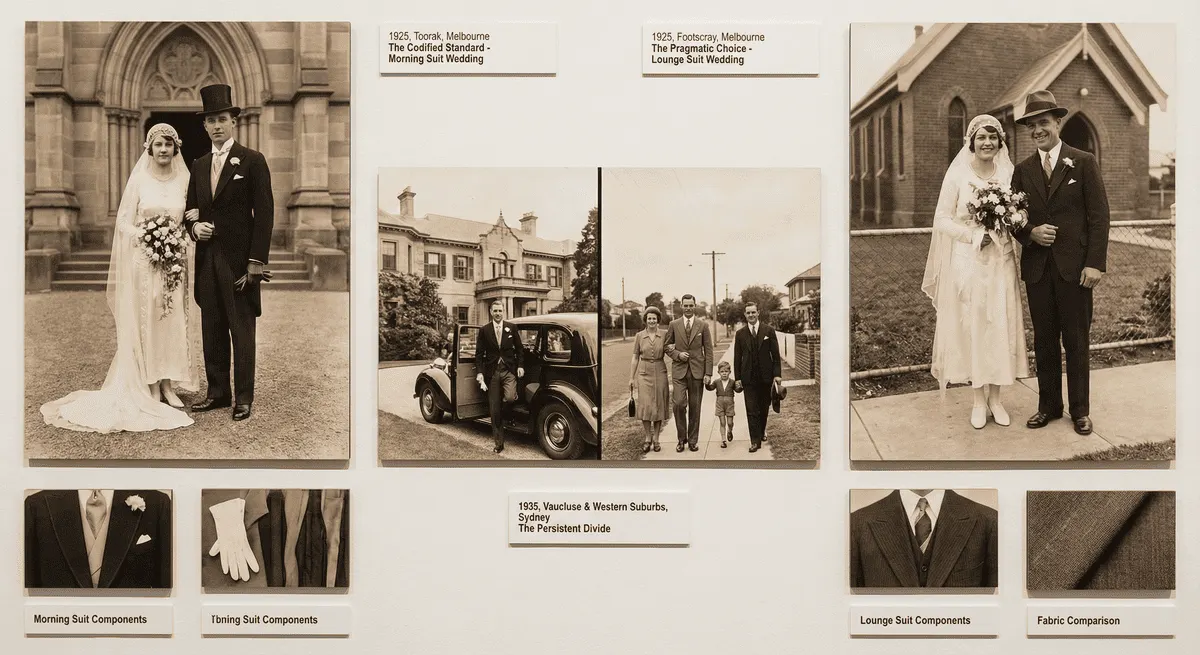

At the beginning of the decade, the wedding uniform for the upper and aspiring middle classes was strictly codified. The Morning Suit consisting of a cutaway coat (usually black or charcoal), striped grey trousers, a dove-grey or buff waistcoat, and a top hat was the non-negotiable standard for a "proper" church wedding. This attire, heavily influenced by the protocols of the British Royal Court, signaled that the groom was a man of substance and respectability. It was a uniform that linked the wearer directly to the Empire.

However, a quiet revolution was occurring in the suburbs and regional towns. The Lounge Suit the ancestor of the modern business suit began to encroach on formal territory. Initially considered casual wear suitable only for the seaside or country, the lounge suit gained acceptance for weddings among the working class due to its practicality and lower cost. By the end of the decade, while the morning coat remained de rigueur for high society events in Toorak (Melbourne) or Vaucluse (Sydney), the lounge suit had become the pragmatic choice for the average Australian male. This shift was not merely aesthetic but economic; a lounge suit could be worn to work or church after the wedding, whereas a morning suit was a single-purpose luxury.

3.2 The Silhouette: From Sausage Casings to Oxford Bags

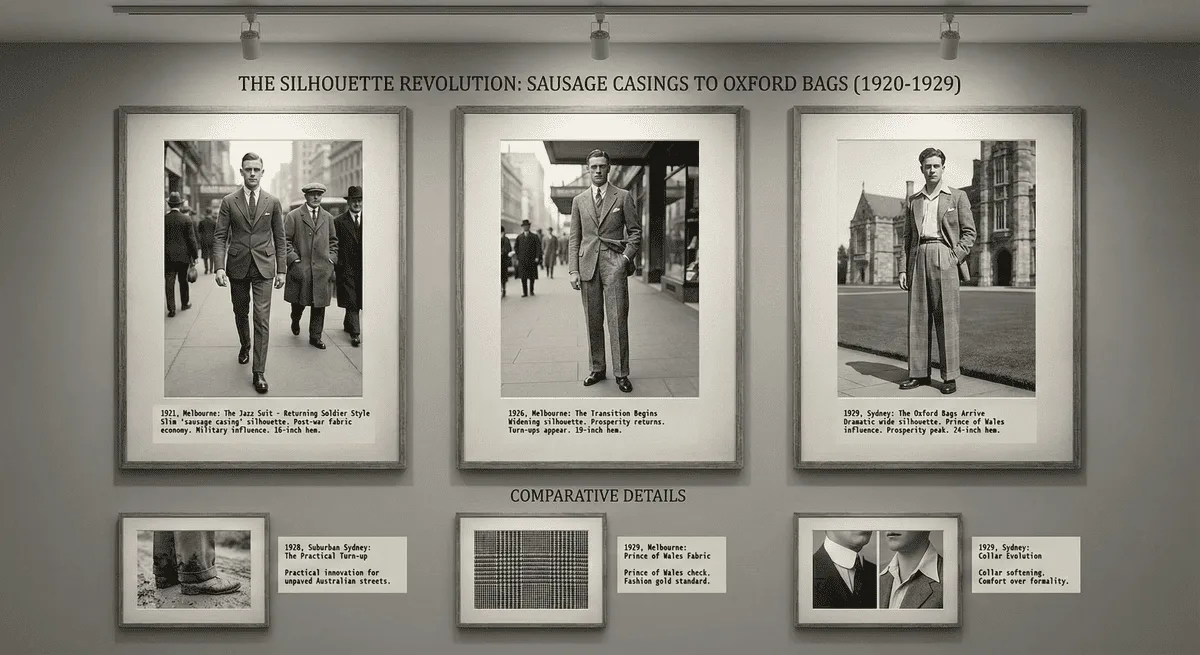

The fit of the 1920s suit underwent a dramatic transformation, mirroring the loosening of social mores.

Early 1920s (The Jazz Suit): Influenced by post-war fabric shortages and the residual aesthetic of military uniforms, suits were cut slim. This "Jazz Suit" or "sausage casing" look featured pinch-back jackets, high waists, and narrow trousers. It was a youthful, almost rebellious look that sharply contrasted with the baggy, heavy coats of the older generation. It was the uniform of the returning soldier who was now young, fit, and eager to shed the bulk of trench warfare gear.

Late 1920s (The Widening): As prosperity returned, so did fabric volume. Trousers expanded into the "Oxford Bag" style, reaching widths of up to 24 inches at the hem. This shift was partly driven by the influence of the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII), whose soft-collared shirts, patterns (like the Prince of Wales check), and cuffed trousers became the gold standard for men’s fashion in Australia. The "turn-up" or cuff became standard, an innovation originally designed to keep trousers out of the mud, which was practical for the unpaved streets of developing Australian suburbs.

3.3 The Dress Reform Debate

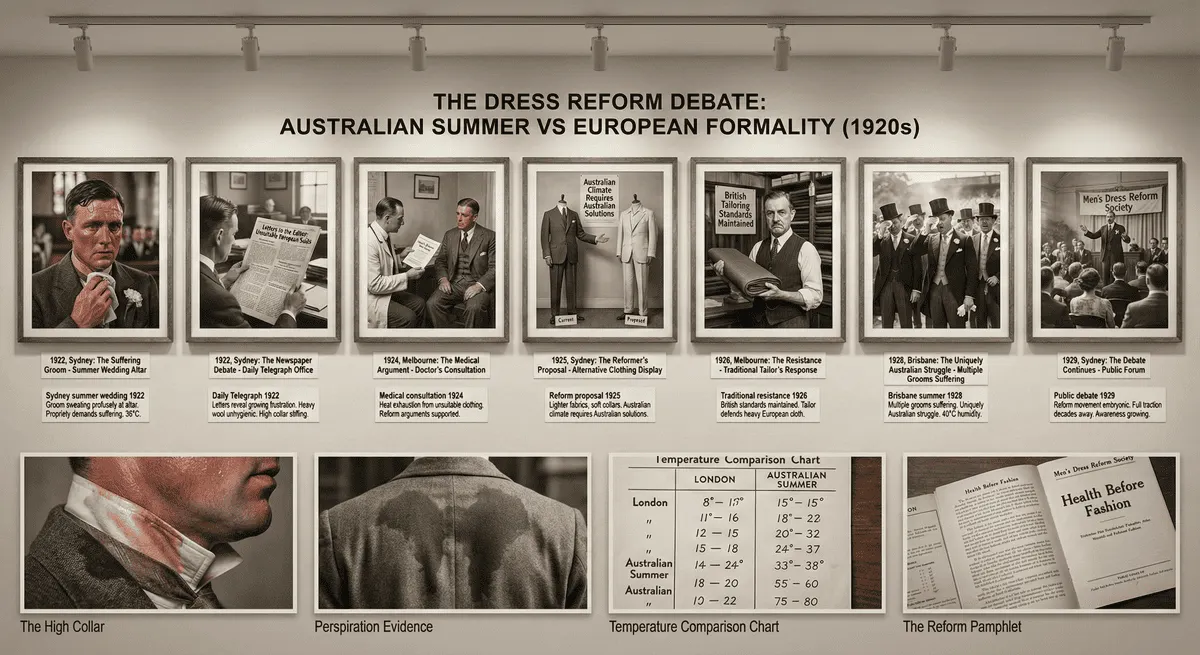

The 1920s also saw the embryonic stages of the Men's Dress Reform movement. Letters to newspapers, such as Sydney’s Daily Telegraph in 1922, reveal a growing frustration with the unsuitability of heavy European suits for the Australian summer. Reformers argued that the high collar and heavy wool were unhygienic and stifling. While this movement would not gain full traction until later decades, it highlighted the uniquely Australian struggle of the groom: sweating profusely at the altar in the name of propriety.

4. The 1930s: The Golden Age of Classic Menswear

Despite the economic devastation of the Great Depression, the 1930s is often cited by fashion historians as the zenith of classic menswear elegance. In Australia, this era solidified the "suit" as the daily uniform for men of all classes, while wedding attire became a bastion of escapist glamour, heavily influenced by the silver screen.

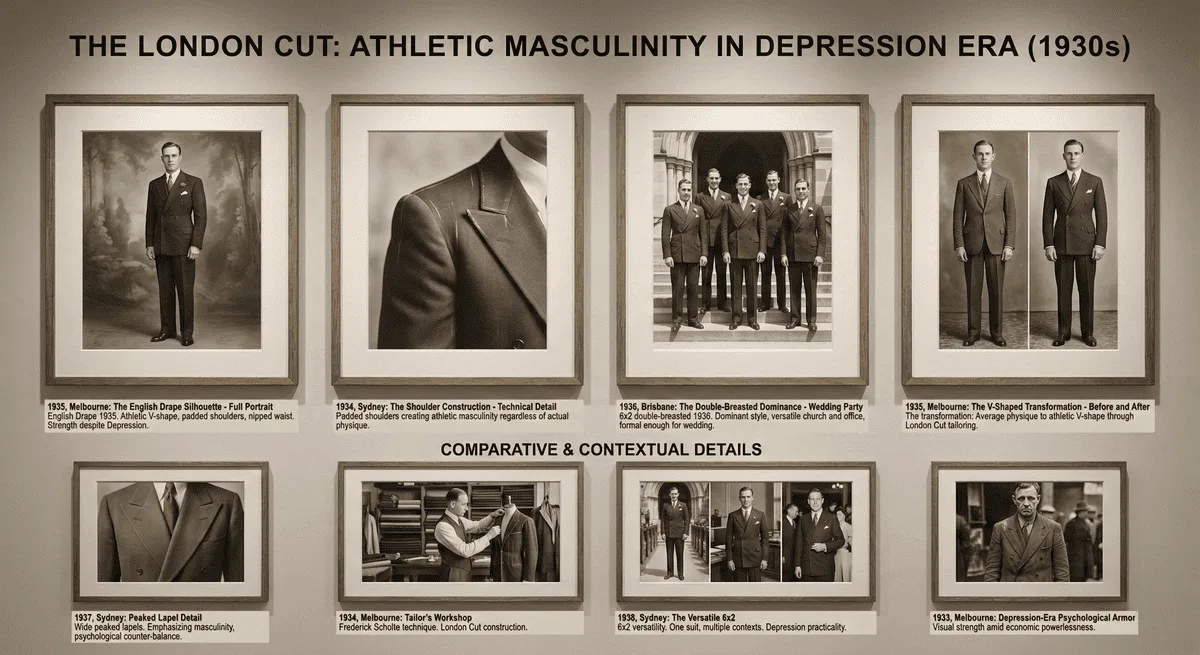

4.1 The "London Cut" and the Drape

The defining silhouette of the 1930s was the "English Drape" or "London Cut," pioneered by the Dutch tailor Frederick Scholte and popularised by the Prince of Wales. This style introduced a fuller chest, broader shoulders, and a nipped waist, creating an athletic V-shaped figure regardless of the wearer's actual physique.

Shoulders and Lapels: Jackets featured padded shoulders and wide, peaked lapels that emphasized masculinity a psychological counter-balance to the economic powerlessness felt by many during the Depression. The visual language of the suit was one of strength and stability.

The Double-Breasted Suit: This became the dominant style for semi-formal weddings. A six-button double-breasted jacket (the 6x2 configuration) in dark navy or charcoal was considered versatile enough for church and office, yet formal enough for a wedding.

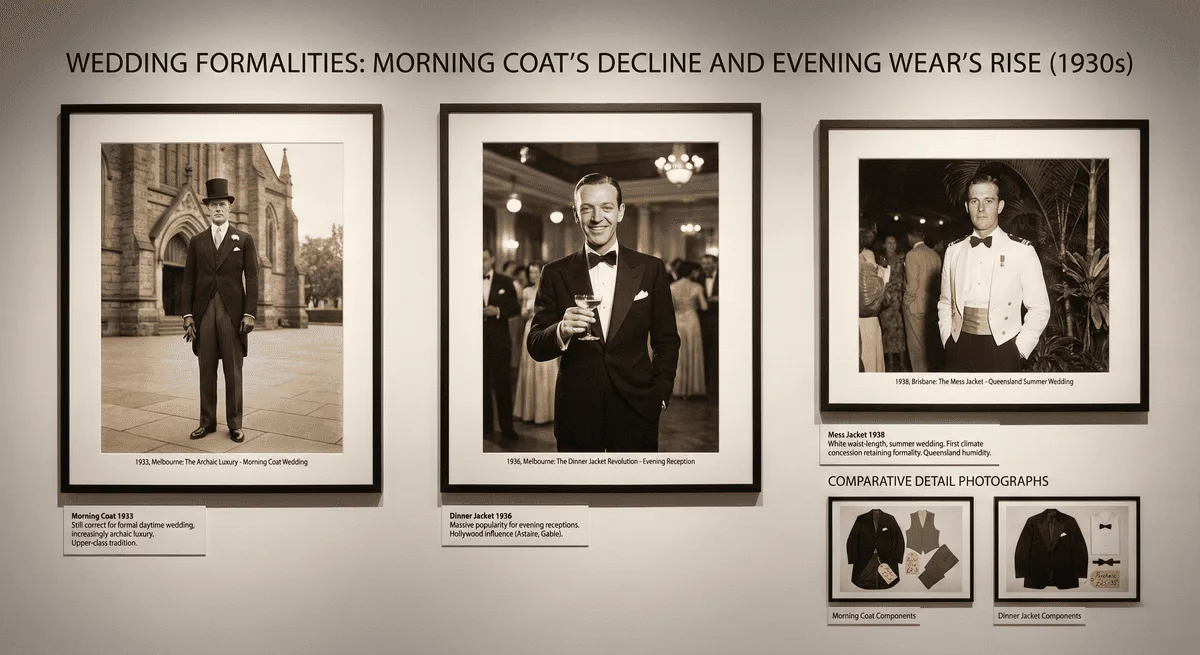

4.2 Wedding Formalities: The Last Stand of the Morning Coat

For weddings, the distinction between day and evening wear was strictly observed, although economic hardship meant fewer men owned these garments.

Daytime: The Morning Coat was still the correct attire for formal weddings, but it was increasingly seen as an archaic luxury. The middle classes began to rent these items rather than purchase them, marking the birth of the formal hire industry in Australia.

Evening: The "Dinner Jacket" (Tuxedo) gained massive popularity for evening receptions, influenced heavily by Hollywood icons like Fred Astaire and Clark Gable. The "Mess Jacket" a short, waist-length jacket often in white enjoyed a brief vogue in Australia for summer weddings, suited to the humid climates of Queensland and New South Wales. This was one of the first concessions to climate that retained a high level of formality.

4.3 The Ivy League Influence

While London remained the primary reference point, the 1930s saw the infiltration of American "Ivy League" styles among younger Australian men. This included the "sack suit" a looser, less constructed garment and the use of lighter colours like cream and tan for summer weddings, particularly in garden settings. The distinction between "Town" (dark, formal) and "Country" (tweeds, lighter colours) became more pronounced, with country weddings allowing for a slightly more relaxed aesthetic.

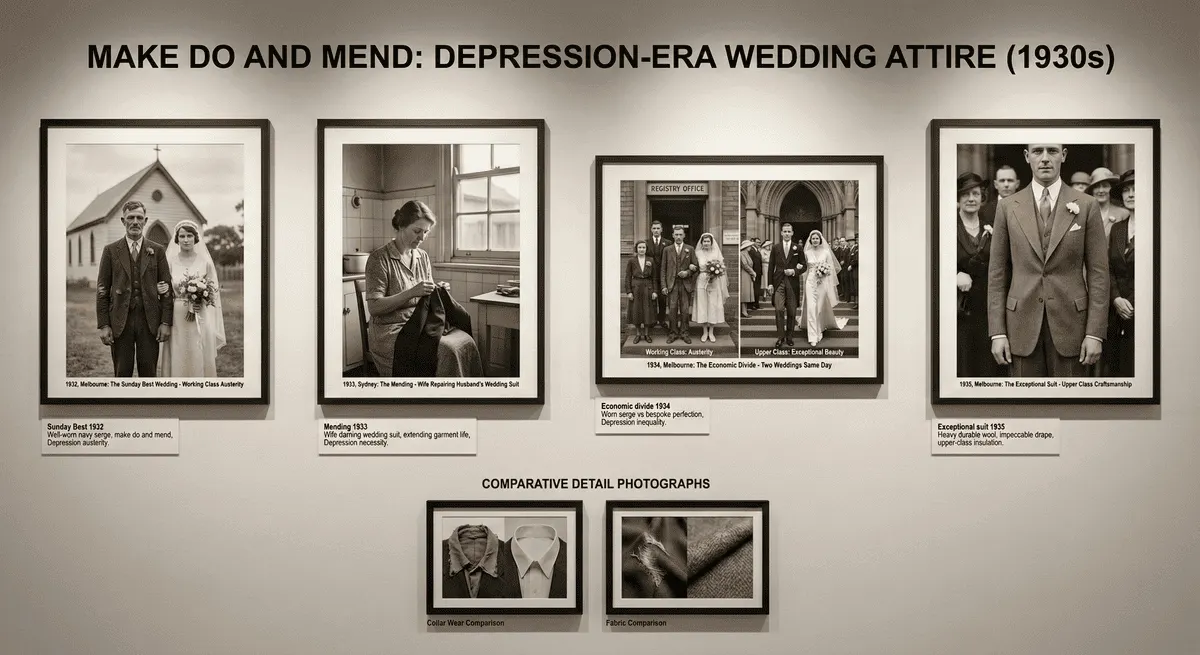

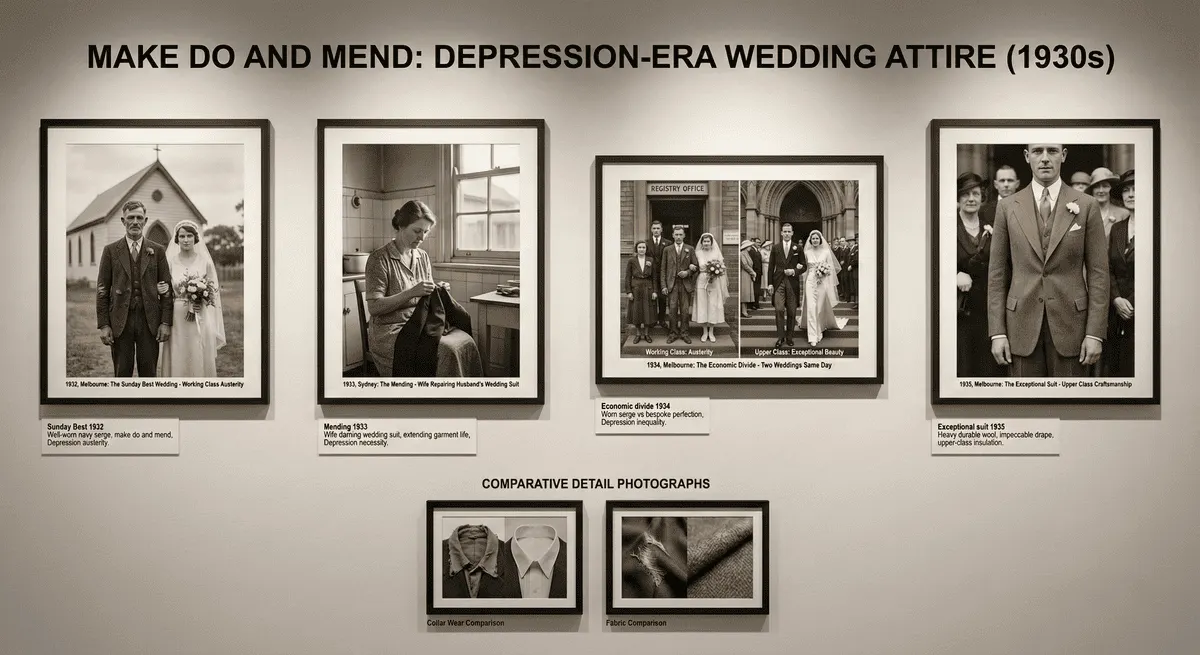

4.4 Economic Impact on Wedding Attire

The Great Depression forced a "make do and mend" philosophy. Many grooms could not afford a new suit and were married in their "Sunday Best" often a well-worn navy serge suit. The widespread unemployment meant that for many, a wedding was a modest affair, and the attire reflected this austerity. However, for those with means, the 1930s suit was a garment of exceptional beauty and construction, using heavy, durable wools that draped impeccably.

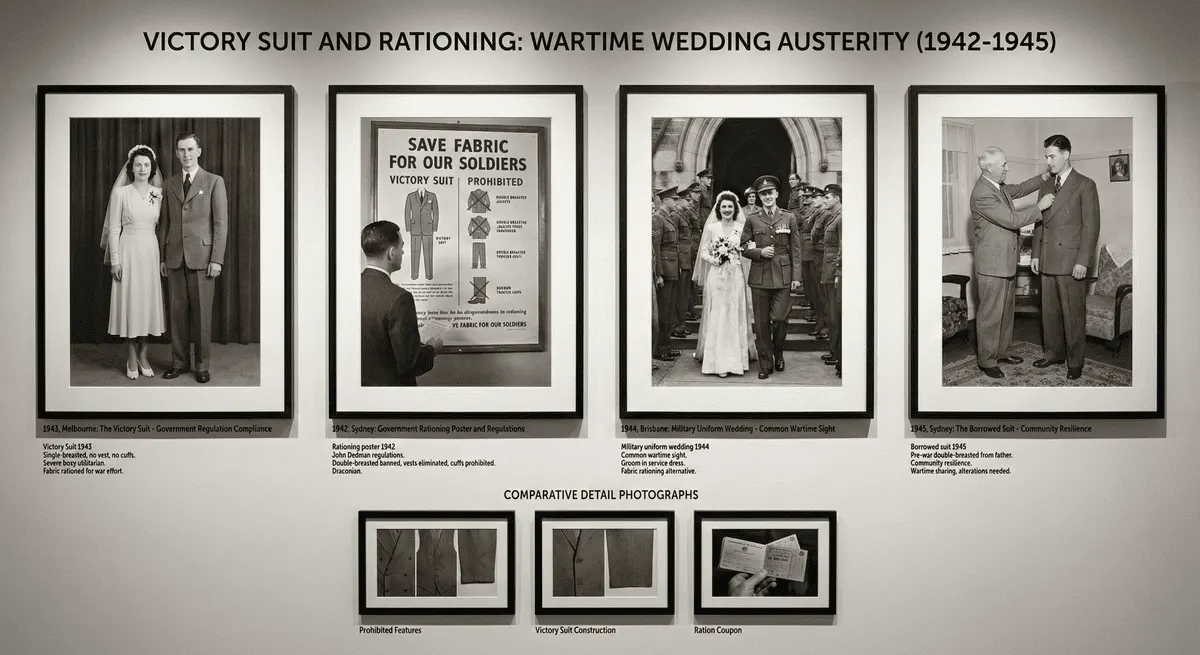

5. The 1940s: Austerity, Rationing, and the Victory Suit

The outbreak of World War II brought the "Golden Age" to an abrupt halt. The fashion landscape of the 1940s in Australia was defined not by style, but by legislation, scarcity, and the overwhelming presence of the military.

5.1 The "Victory Suit" and Rationing Regulations

In 1942, the Australian government, led by Minister for War Organization of Industry John Dedman, introduced strict clothing rationing. The "Victory Suit" was a minimalist garment designed to save fabric for the war effort. The regulations were draconian and fundamentally altered the look of the Australian male:

- Elimination of Waste: Double-breasted jackets were banned because the overlap of fabric was considered wasteful. Waistcoats (vests) were deemed non-essential and removed from the standard three-piece suit. Trouser cuffs (turn-ups) were prohibited, as they used unnecessary inches of cloth.

- The Silhouette: Suits became single-breasted, shorter in the jacket, and narrower in the trouser. The look was severe, boxy, and utilitarian.

- Coupons: A man was allotted a specific number of coupons per year. A suit might cost a significant portion of these, making a new wedding suit an impossibility for many. Grooms often married in their military service uniforms a common sight in 1940s wedding photography or borrowed pre-war suits from relatives. The "borrowed suit" became a symbol of community resilience.

5.2 The American Influence and the Zoot Suit

While local production was restricted, the arrival of thousands of American GIs in Australia introduced a counter-aesthetic. The Americans wore their uniforms with a relaxed, loose fit that contrasted with the stiff British drill. This exposure, combined with the "Zoot Suit" subculture (long jackets, baggy trousers) bubbling in the US, began to influence Australian street style. While the Zoot Suit itself was largely kept out of weddings due to its association with rebellion and the "black market," it planted the seeds for a looser, more American silhouette in the post-war years.

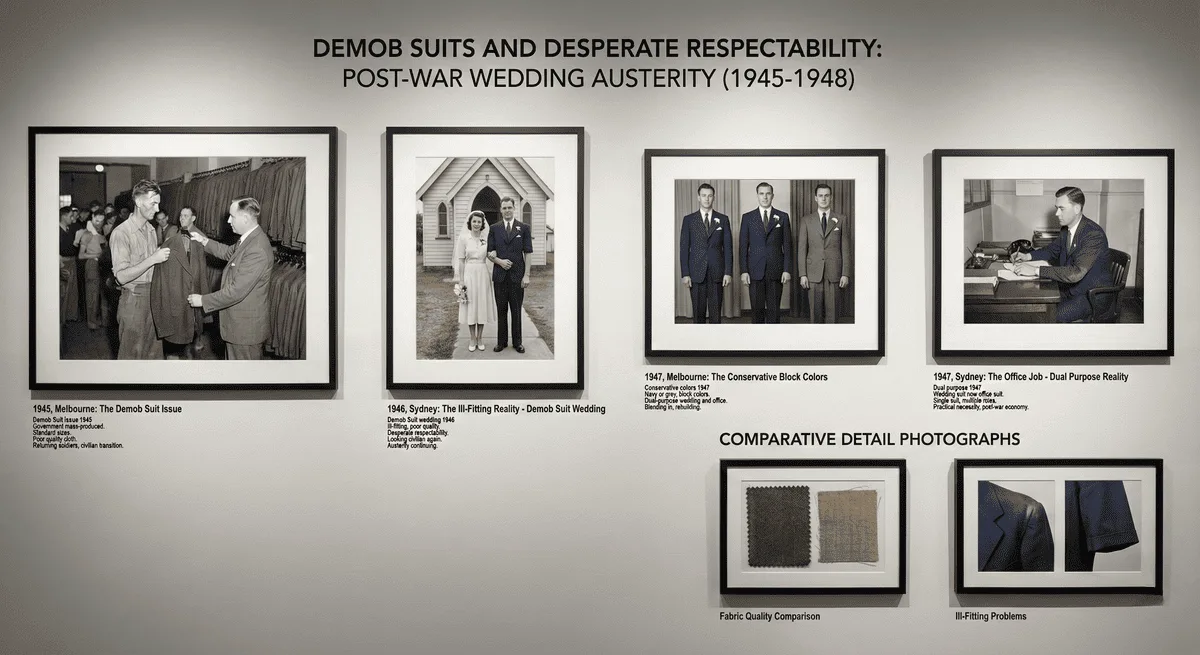

5.3 Demobilization Fashion

Post-1945, the "Demob Suit" (issued to soldiers upon demobilization) became the default wedding suit for thousands of returning men. These suits were often mass-produced, ill-fitting, and made of poor quality cloth due to ongoing shortages. The aesthetic of the immediate post-war wedding was one of desperate respectability men sought to look like civilians again, favoring conservative, block-colored suits in navy or grey that could serve a dual purpose for their new office jobs. The flamboyance of the 1930s was gone, replaced by a desire to blend in and rebuild.

5.4 The Wedding Dress vs. The Suit

Interestingly, while men's suits were heavily rationed, women often pooled coupons to create elaborate wedding dresses, or used non-rationed materials like parachute silk. This created a visual disparity in 1940s wedding photos: a bride in a relatively glamorous, improvised gown standing next to a groom in a severe, utility suit or a uniform.

6. The 1950s: The Grey Flannel Suit vs. The Rocker

The 1950s in Australia was a period of economic boom, suburban sprawl, and the "Baby Boom." The wedding suit of this era reflected the desire for security and conformity, characterized by the "Man in the Grey Flannel Suit" archetype, but it was also the decade where youth culture began to fracture the sartorial consensus.

6.1 The Conservative Cut

The typical 1950s wedding suit was single-breasted with relatively narrow lapels and a "sack" cut a straighter, less fitted shape that prioritized comfort over the athletic drape of the 30s.

- Fabrics: The introduction of synthetic blends (polyester, rayon) began to change the texture of suits. These fabrics were marketed as "miracle cloths" that resisted wrinkling a significant selling point for the Australian groom in summer.

- Colour: Sombre tones ruled. Charcoal, navy, and arguably the most popular, medium grey. Weddings were serious, formal affairs, often taking place in the morning followed by a "breakfast." The groom was expected to look like a responsible provider.

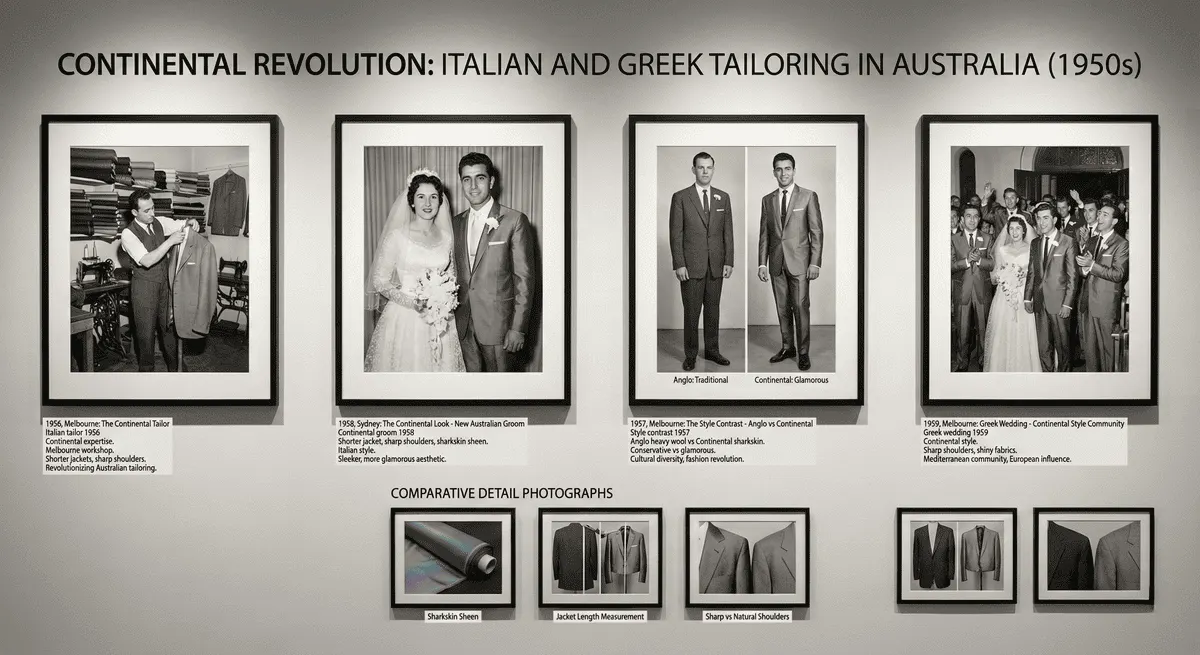

6.2 The Continental Influence

Migration from Italy and Greece in the 1950s revolutionized Australian tailoring. These migrants brought with them the "Continental" look: shorter jackets, sharper shoulders, and shinier fabrics like sharkskin. While Anglo-Australian grooms stuck to heavy wools and conservative cuts, "New Australian" grooms introduced a sleeker, more glamorous aesthetic. They were not afraid of color or sheen, and their influence would slowly bleed into the mainstream, challenging the dominance of the British cut.

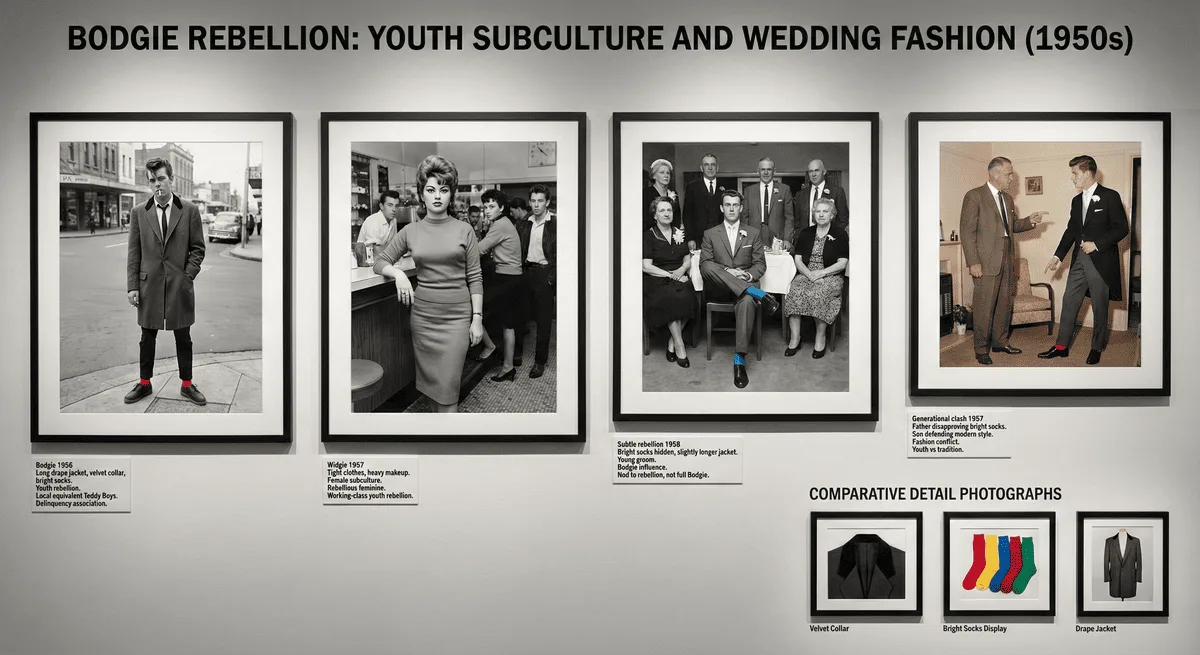

6.3 Subcultures: Bodgies and Widgies

The 1950s saw the rise of the "Bodgie" (male) and "Widgie" (female) subculture in Australia the local equivalent of the Teddy Boys or Greasers. While Bodgies were associated with delinquency, their fashion long drape jackets, velvet collars, and bright socks began to influence the younger generation of grooms. A young groom might sneak a pair of brighter socks or a slightly longer jacket into his wedding ensemble as a nod to this rebellion, even if he didn't go the full "Bodgie."

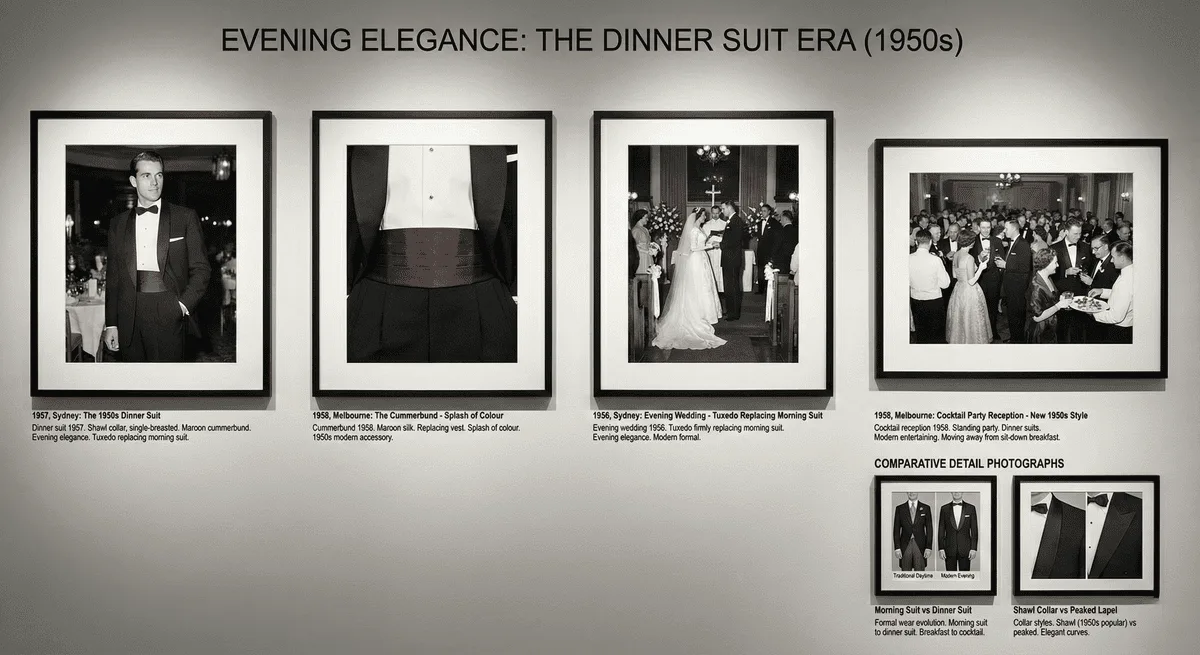

6.4 The Dinner Suit (Black Tie)

By the 1950s, the tuxedo had firmly replaced the morning suit for evening weddings. The style was often shawl-collared and single-breasted. The cummerbund became a popular accessory, replacing the vest and allowing for a splash of colour (usually maroon or black). This was the era of the "Cocktail Party" wedding reception, moving away from the sit-down breakfast, which required a shift to evening wear.

7. The 1960s: The Peacock Revolution and the Mod Groom

The 1960s marked the shattering of the conservative mold. Triggered by the Beatles' tour of Australia in 1964 and the global youthquake, men’s fashion moved from "fitting in" to "standing out."

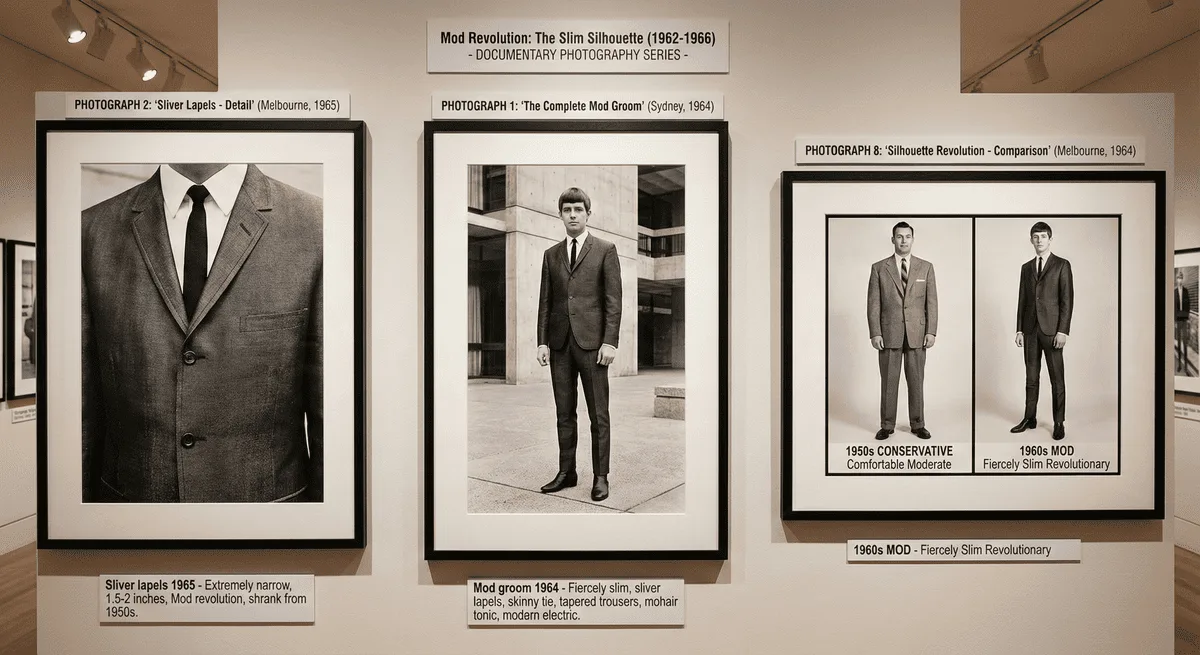

7.1 The Mod Silhouette

The early-to-mid 60s saw the "Mod" look dominate, particularly in urban centres like Sydney and Melbourne. Suits became fiercely slim.

- The Details: Lapels shrank to slivers. Ties became skinny. Trousers were tapered to the ankle and devoid of cuffs. Jackets were cut short, often with three or four buttons.

- Fabric: Mohair became the fabric of choice for the fashionable groom. Its slight sheen ("tonic" suits) and crisp texture epitomized the modern, "electric" feel of the decade. The two-tone iridescence of tonic fabric was particularly prized.

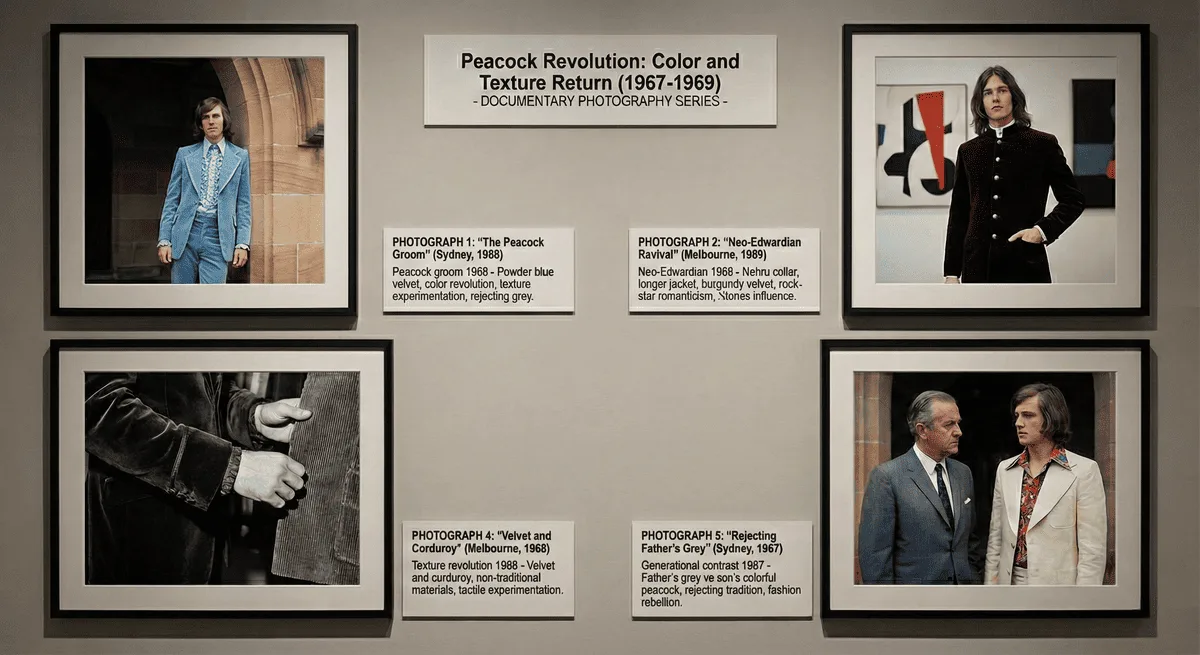

7.2 The Peacock Revolution

By the late 1960s, the "Peacock Revolution" arrived. Men reclaimed colour and texture, rejecting the drab greys of their fathers.

- Experimentation: Wedding suits appeared in non-traditional materials like velvet and corduroy. Colours shifted from greys to powder blues, creams, and even burgundies.

- The Edwardian Revival: Curiously, there was a brief revival of "Neo-Edwardian" styles longer jackets with Nehru collars or velvet collars, worn by the avant-garde groom who wanted to mix historical romanticism with rock-star swagger. This look was popularised by bands like The Rolling Stones and quickly adopted by trendy Australian grooms.

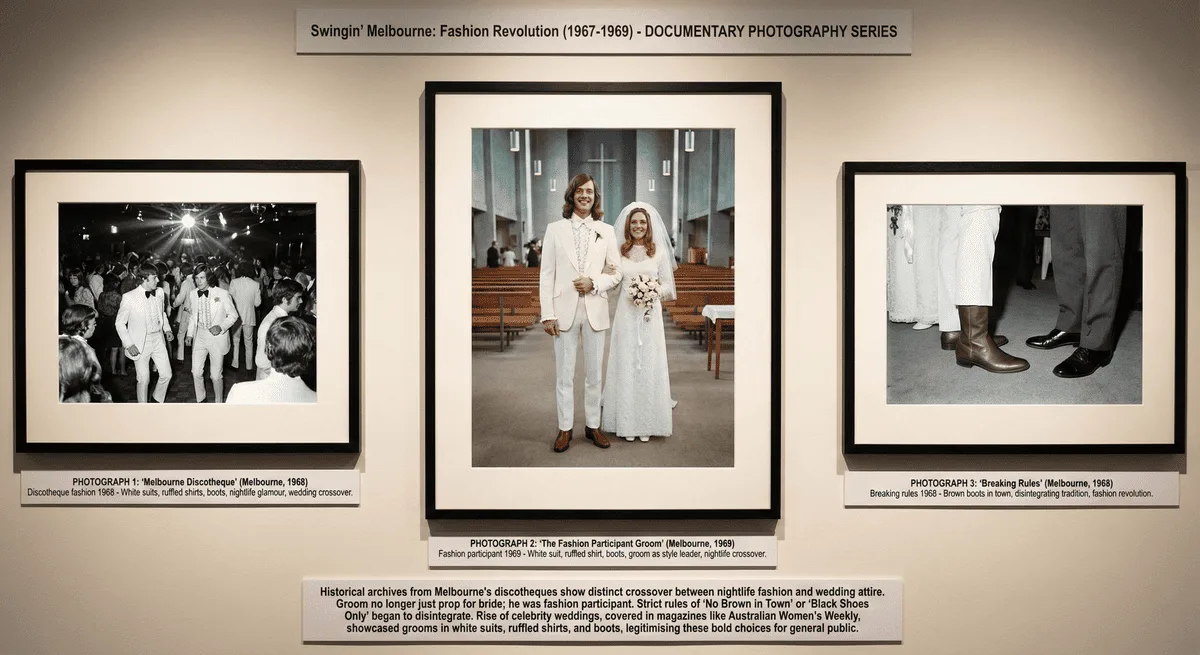

7.3 The "Swingin' Melbourne" Scene

Historical archives from Melbourne's discotheques show a distinct crossover between nightlife fashion and wedding attire. The groom was no longer just a prop for the bride; he was a fashion participant. The strict rules of "No Brown in Town" or "Black Shoes Only" began to disintegrate. The rise of celebrity weddings, covered in magazines like Australian Women's Weekly, showcased grooms in white suits, ruffled shirts, and boots, legitimising these bold choices for the general public.

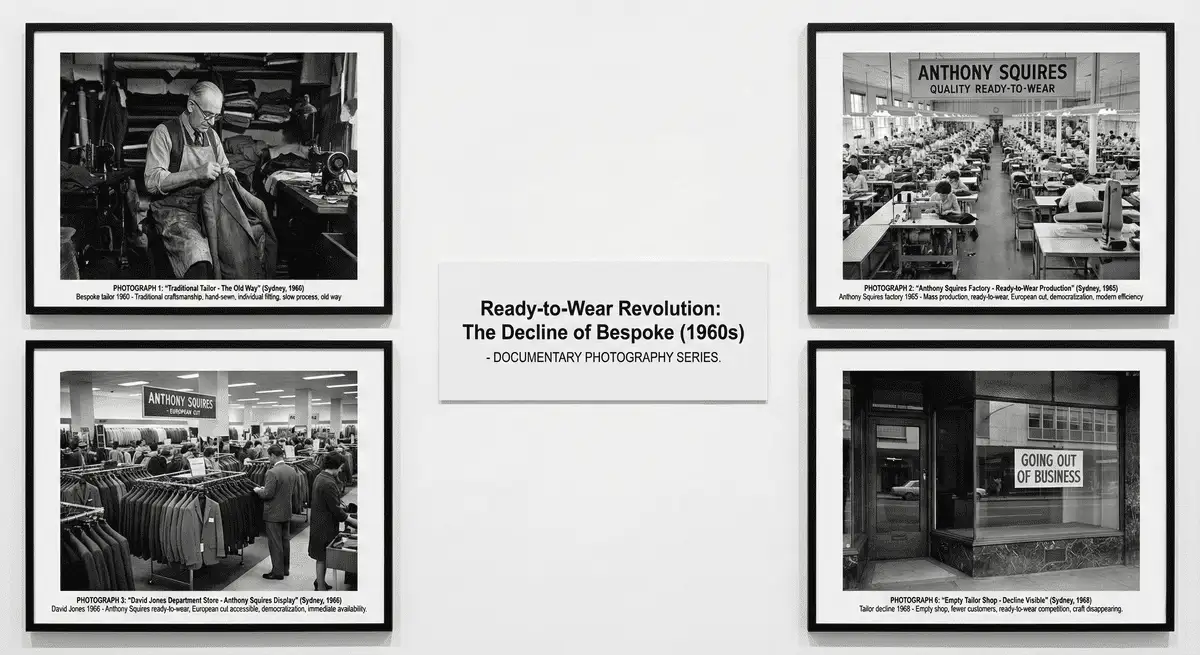

7.4 The Decline of Bespoke

The 1960s also marked a significant shift in the production of suits. The rise of high-quality ready-to-wear suits from brands like Anthony Squires meant that fewer men were going to traditional tailors. Anthony Squires, established in 1948, became an icon of Australian tailoring, dressing Prime Ministers and executives, and offering a "European" cut that was accessible in department stores like David Jones. This democratisation meant that the latest trends could be adopted much faster than in the bespoke era.

8. The 1970s: Disco, Ruffles, and the Anti-Suit

If the 1960s broke the rules, the 1970s rewrote the rulebook in neon. This decade is often looked back upon with derision, but it represented a significant moment of liberation for men’s wedding attire.

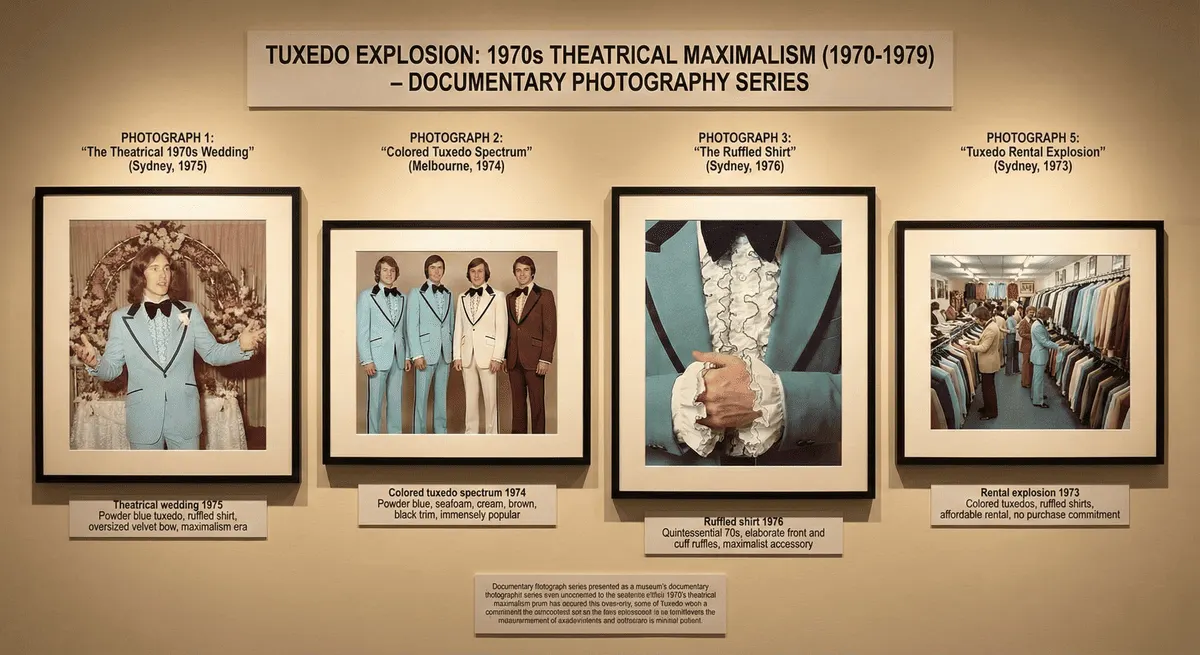

8.1 The Wedding Tuxedo Explosion

The 1970s wedding was often a theatrical event. The classic black tuxedo was frequently jettisoned for:

- The Coloured Tuxedo: Powder blue, seafoam green, cream, and brown tuxedos were immense popular trends. These were often trimmed with black velvet or satin piping. The rental market exploded, allowing grooms to wear these outlandish styles without the commitment of purchase.

- The Ruffled Shirt: The quintessential 70s accessory. Wedding shirts featured elaborate ruffles down the front and at the cuffs, often paired with oversized butterfly bow ties in velvet. This was the era of "maximalism".

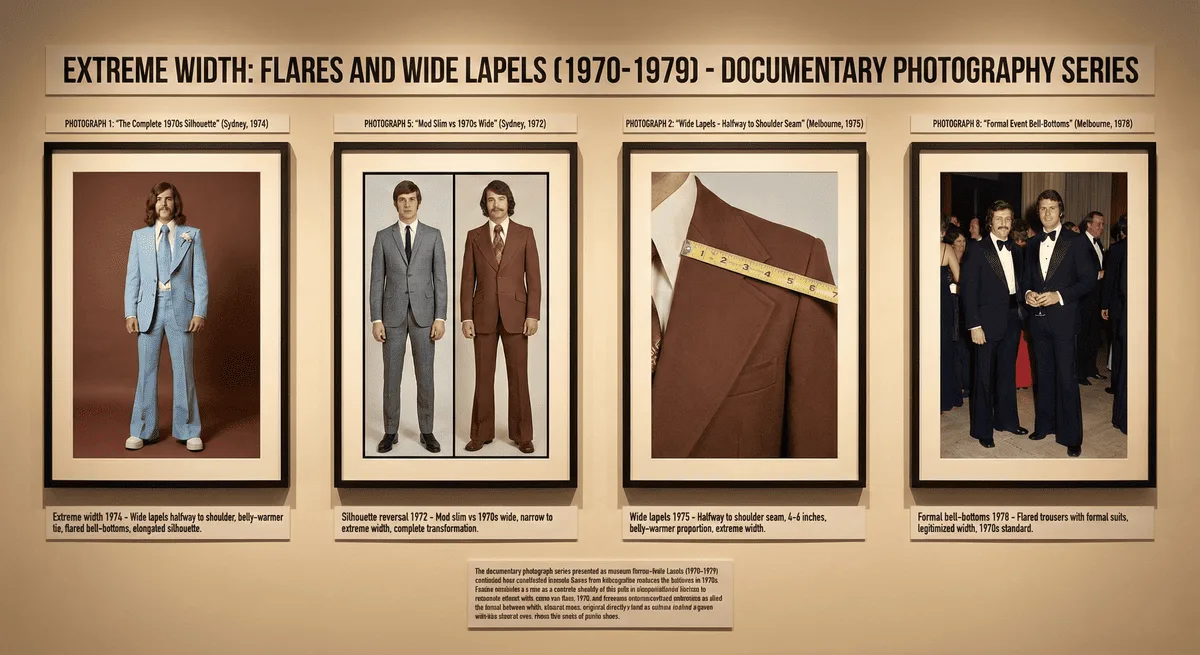

8.2 Flares and Wide Lapels

The silhouette swung from the skinny Mod look to extreme width.

- Lapels: "Belly-warmer" ties and lapels that extended halfway to the shoulder seam were standard.

- Trousers: Flared trousers or "bell-bottoms" were worn even with formal suits. High-waisted pants with tight hips and wide hems created a distinct, elongated silhouette.

8.3 The "Safari Suit" Phenomenon

The 1970s also saw the rise of the Safari Suit as a uniquely acceptable semi-formal option in Australia. Famous for being worn by South Australian Premier Don Dunstan, the safari suit short-sleeved jacket, matching trousers or shorts, usually in beige, powder blue, or cream offered a climate-appropriate alternative to the wool suit. For less formal weddings, particularly in summer, the safari suit was considered smart, modern, and practical. It was a rejection of the British "stiff upper lip" in favour of Australian pragmatism.

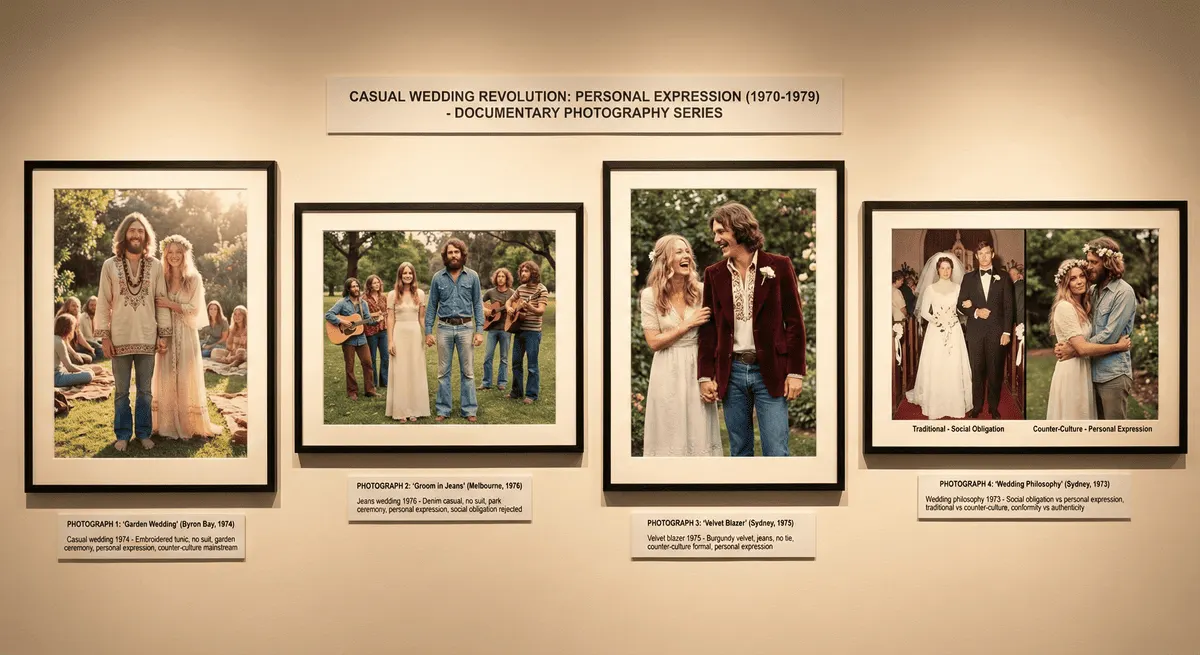

8.4 The "Casual" Wedding

The counter-culture "hippie” movement filtered into the mainstream, leading to garden and park weddings where the groom might abandon the suit entirely for embroidered tunics, jeans, or velvet blazers. This was the beginning of the "wedding as personal expression" rather than "wedding as social obligation”.

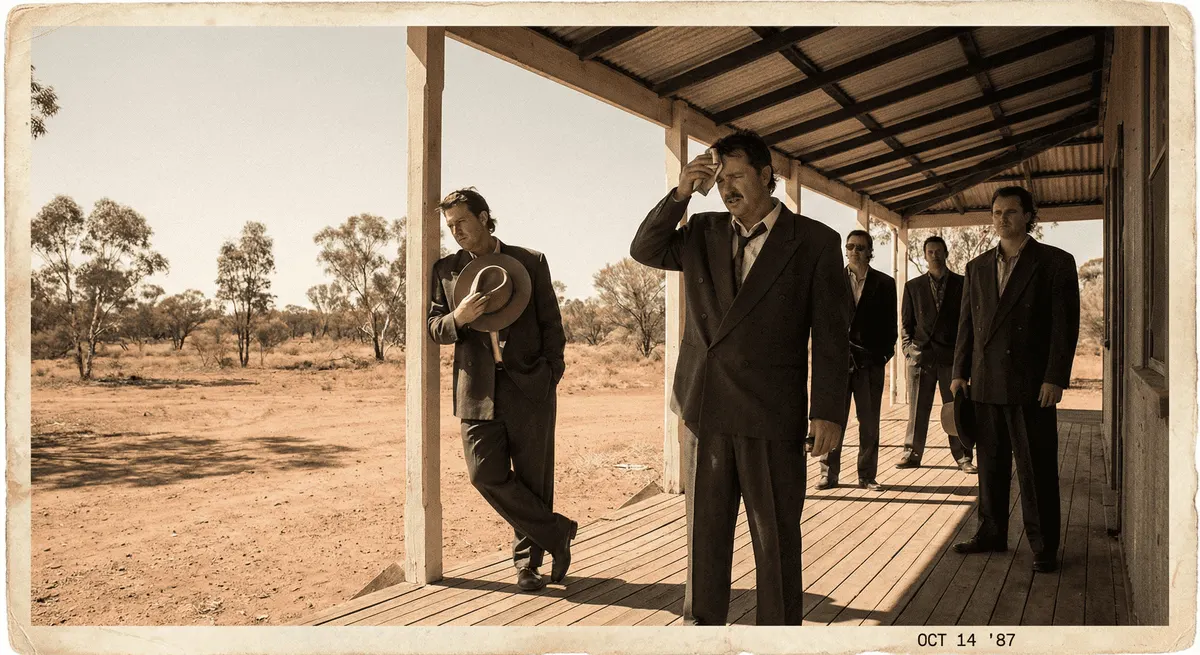

9. The 1980s: Power Dressing and the Corporate Groom

The 1980s was the era of "Greed is Good," and wedding fashions reflected the economic boom and the rise of the corporate warrior.

9.1 The Power Suit

Influenced by Italian designers like Giorgio Armani and the "Wall Street" aesthetic, the suit silhouette expanded again.

- Structure: Huge, padded shoulders and a loose, unconstructed drape became the norm. The "Power Suit" was designed to occupy space and project dominance. The jacket was long, the gorge was low, and the fit was generous.

- Double-Breasted Return: The double-breasted suit made a massive comeback, this time with a lower button stance and wide peak lapels.

9.2 The Shiny Suit Phenomenon

Synthetic fabrics reached their peak in the 80s. Wedding suits often featured a "sheen" shiny grey or silver fabrics, often blends of wool, silk, and polyester, were incredibly popular for groomsmen. This was the era of the "hire suit" industry booming, where grooms would rent identical, often ill-fitting, shiny suits for their entire party. The "shiny suit" became a signifier of a "fancy" occasion, distinct from the matte wool of the office.

9.3 The "New Romantic" and Vintage Revival

Paradoxically, the 80s also saw a nostalgic "New Romantic" movement. Grooms looked back to the 1920s and Victorian eras, incorporating wing-collar shirts, cravats, and even top hats into their wedding ensembles. However, these historical elements were often stylised with 80s fabrics and grooming, creating a unique hybrid aesthetic. The influence of the televised wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer (1981) cannot be overstated; it revived the "fairy tale" wedding, bringing back tails and formal morning suits for the upper end of the market.

9.4 Australian Brands: Stafford Ellinson and Lowes

At the mass-market level, brands like Lowes and Stafford Ellinson dominated. Stafford Ellinson, owning the Anthony Squires label, manufactured thousands of suits in Australia, employing a large workforce. This was the last great decade of Australian domestic clothing manufacturing before the tariff reductions of the 90s decimated the local industry. The availability of affordable, locally made suits meant that almost every Australian groom could afford to buy, rather than rent, if he chose.

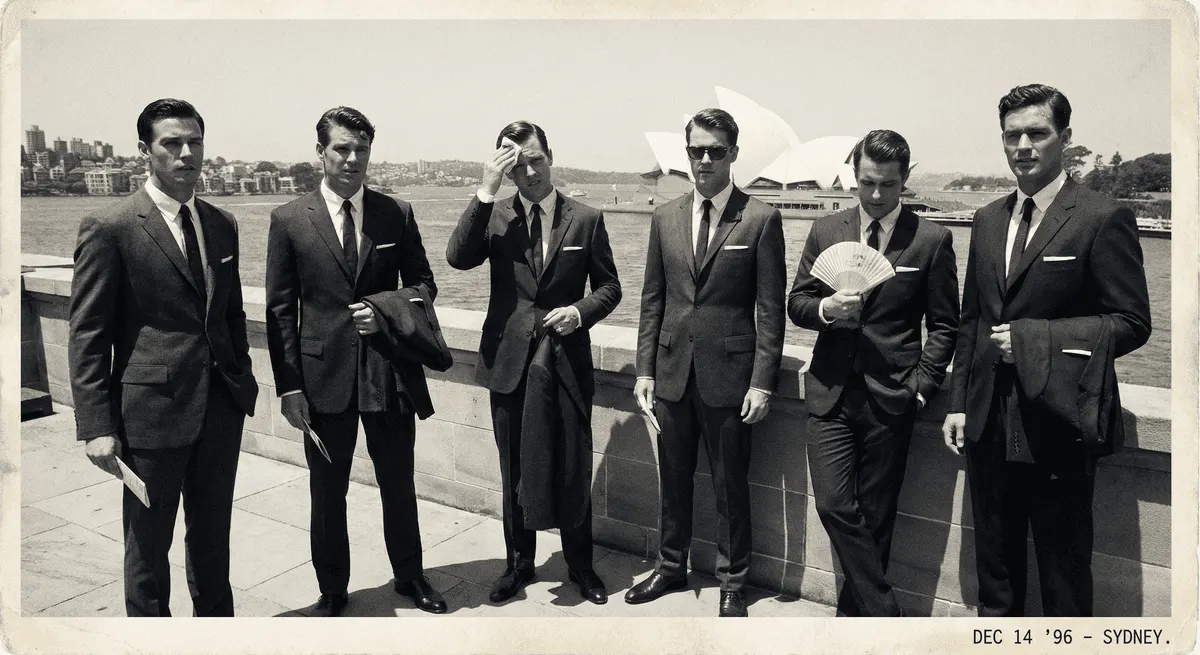

10. The 1990s: Minimalism and the "Recession" Suit

Following the stock market crash of 1987 and the recession of the early 90s, the excess of the 80s was stripped away. The 90s aesthetic was defined by minimalism, influenced by designers like Helmut Lang, Jil Sander, and Calvin Klein.

10.1 The Three-Button Suit

The quintessential 90s wedding suit was a single-breasted, three-button jacket. The button stance was high, the lapels were narrow, and the fit was boxy and loose.

- Colour: Black became the overwhelming favorite. The "Reservoir Dogs" look black suit, white shirt, skinny black tie became a wedding staple for the "cool" groom. This was a rejection of the shiny, coloured suits of the 80s.

- Fabric: Matte finishes replaced the 80s shine. Crepe wools and flat gabardines were preferred. The aim was "understated cool."

10.2 Grunge Influence

While not "formal," the Grunge movement fostered a "can't be bothered" attitude that bled into formal wear. Suits were often worn ill-fitting, trousers pooled at the shoes, and grooming was deliberately unkempt. This was the decade where the groom often looked like he had been forced into his suit by his parents. The "prom suit" look oversized and rented was common even at weddings.

10.3 Australian Designer Emergence: Morrissey Edmiston

The 90s saw the rise of specific Australian designers who catered to a sharper, more fashion-forward crowd. Morrissey Edmiston defined the "Sydney look" with sharp, sexy, somewhat retro-inspired tailoring that offered an alternative to the boxy department store suit. Their suits were worn by celebrities and the social elite, influencing the high end of the wedding market towards a sexier, more body-conscious aesthetic long before Hedi Slimane made it global.

10.4 Country Road and the Middle Market

Country Road cemented its place in the 90s as the purveyor of "lifestyle" clothing. While not a traditional suit maker, they popularized the "separate" look chinos and a navy blazer which became acceptable for semi-formal weddings. The brand's ubiquitous canvas duffle bags and chambray shirts represented a uniquely Australian "preppy" look that was relaxed but aspirational.

11. The 2000s: The Slim Fit Revolution and "Metrosexuality"

The new millennium brought a return to tailoring and body-conscious fits. The influence of Hedi Slimane cannot be overstated he single-handedly slimmed down the male silhouette globally, and Australian men eventually caught up.

11.1 The Skinny Suit

By the mid-2000s, the boxy 90s fit was dead. Wedding suits became skin-tight.

- Trousers: Low rise and very slim leg. Jackets: Shorter, one or two buttons, with high armholes. Ties: The "skinny tie" returned with a vengeance.

- Culture: The concept of "Metrosexuality" made it acceptable for straight men to care deeply about grooming, skincare, and the fit of their suit. Grooms began to outshine brides in their attention to sartorial detail.

11.2 The Rise of M.J. Bale (2009)

The end of the decade saw a pivotal moment in Australian menswear: the founding of M.J. Bale by Matt Jensen in 2009. Jensen identified a gap in the market: Australian men had access to cheap, fused suits or expensive international luxury, but nothing in the middle. M.J. Bale championed the "Superfine Merino" suit, educating Australian men on the importance of fabric quality and provenance. They worked directly with Tasmanian wool growers to create a "paddock to palm" narrative. This brand almost single-handedly raised the standard of the average Australian wedding suit, making the navy blue Merino wool suit the new national uniform.

11.3 The "Festival Chic" and Boho Influence

Parallel to the slim suit, the "Boho" trend began to emerge, influenced by festivals like Coachella. "Festival Chic" weddings saw grooms wearing vests without jackets, braces, and fedoras. This was the precursor to the "rustic" explosion of the 2010s.

12. The 2010s: The Heritage Revival and the "Rustic" Groom

The 2010s saw a massive shift away from the "shiny hotel ballroom" wedding to the "rustic barn/winery" wedding. This change in venue necessitated a change in dress.

12.1 The "Peaky Blinders" and "Mad Men" Effect

Pop culture drove a massive resurgence in "heritage" fabrics.

- Tweed and Texture: Grooms began wearing tweed three-piece suits, houndstooth, and checks. The "shiny" suit was now considered the height of bad taste.

- The Bow Tie: The bow tie returned, not as a formal black-tie accessory, but in fun patterns, timber, or leather, worn with suspenders and often without a jacket.

- Colours: Navy remained king, but lighter blues, tans, and even greens became popular.

12.2 The "Hipster" Groom

The "Hipster" subculture brought beards, tattoos, and vintage styling to the altar. The groom might wear a floral tie, a tie bar, and brown brogues without socks. The look was "curated authenticity."

12.3 The Custom Tailoring Boom: P. Johnson and Institchu

The 2010s saw the democratization of "Made-to-Measure" (MTM).

- P. Johnson: Founded by Patrick Johnson in 2009, this brand pioneered a "soft tailoring" look unstructured jackets with no padding that was perfectly suited to the Australian climate and the relaxed, affluent lifestyle. Johnson taught Australian men that a suit didn't have to be stiff to be formal. His aesthetic became the benchmark for the wealthy groom.

- Institchu: Offered a lower price point MTM service, allowing grooms to design every element of their suit online. This killed the rental market; why rent an ill-fitting tux for $200 when you could buy a custom suit for $600?

13. The 2020s (to Present): Post-Pandemic Individualism and Linen

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the wedding industry and accelerated the trend towards smaller, more intimate, and less formal ceremonies.

13.1 The "Broken" Suit and the Victory of Linen

In the 2020s, the idea of a "suit" (matching jacket and trousers) is optional.

- Linen: Finally, after a century of struggle, Australian men have fully embraced linen for weddings. Brands like M.J. Bale and P. Johnson push high-quality, crush-resistant linen suits in tobacco, olive, and oatmeal tones. The fear of "wrinkles" has been replaced by an appreciation for "sprezzatura."

- Separates: The "Spezzato" (broken suit) look wearing a jacket of one colour with trousers of another is widely accepted for grooms, allowing for greater re-wearability.

13.2 Black Tie Resurgence

Conversely, for city weddings, there is a trend towards "hyper-formality" as a reaction to the sweatpants-wearing pandemic years. The "Black Tie Optional" code has become popular, encouraging guests and grooms to dress up in dinner suits, but often with modern twists like velvet jackets or slippers.

13.3 Cultural Idiosyncrasies: Eagle Rock and R.M. Williams

- Eagle Rock: A peculiar modern tradition at many Australian weddings involves the song "Eagle Rock" by Daddy Cool (1971). When played, it is customary for men on the dancefloor to drop their trousers and dance in a squatting position. This larrikin element underscores the Australian refusal to take formality too seriously.

- R.M. Williams: The R.M. Williams Craftsman boot has become the only acceptable "work boot" to wear with a suit. In the last 20 years, it has transitioned from farm wear to the boardroom and the altar. For many Australian grooms, a pair of polished Chestnut or Black RMs is as essential as the ring.

14. Conclusion

The evolution of men's wedding suits in Australia is a mirror of the nation's journey towards self-assurance.

Bridge the Century of Style with a Masterpiece Made Only for You

From the rigid British traditions of the 1920s to the effortless linen elegance of the modern era, the Australian groom has always balanced heritage with the unique spirit of the Land Down Under. Your wedding isn't just an event; it’s your moment to step into this storied lineage of sartorial excellence.

Are you ready to write your own chapter in fashion history? Discover our bespoke & custom-made wedding suit services, where we blend a century of Australian inspiration with world-class tailoring. Whether you’re looking for the sharp "English Drape" of the Golden Age, the soft "Sprezzatura" of contemporary linen, or a ruggedly elegant look paired with your favorite R.M. Williams boots, we craft garments that don't just fit your body—they tell your story.